The unnamed narrator retreats to

a coffee house every day to escape from the unsettling atmosphere of crisis at

home. In the Coffee House, the serving waiter Vincent seems to the narrator, a

wise being who knows secrets of his internal chaos and can put them into a

calming virtue of words. The novel opens in one such day, when the narrator

finds himself in the coffee house again, only this time he hasn't returned to

his home for more than thirty hours, where his wife is expected to return but

hasn't. He broods over his failed relationship with a girl at the coffee with

whom he had suddenly cut off his ties, but more than that he's there to tell

all about his family.

In the following chapters he

takes us into the roots of his family, its members and their characters. His

family consists of his parents, Chikkappa (Uncle), Malati (Sister) and Anita

(Wife). They now own a business, and are well enough, such that the narrator

doesn't have to work at all if he wishes to, only that because of his wife he

completes the formality of going to work, where he does almost nothing. Chikkappa

runs the business, suffers the toil and brings the wealth home to everyone's

delight. They weren't always like this; they once had been a family with meager

income, and lived in a poor lower-middle-class quarter in an ant1

infested house, and they'd moved to the present luxury only after new wealth

entered their family.

1. We

had two types of ants at home. One was a small brisk-moving black variety that

appeared only occasionally. But when it did, it came in an army numbering

thousands. These ants wandered everywhere in apparent confusion, always bumping

heads and pausing before realizing something and rushing off in random

directions. They had no discernible purpose in life other than trying our

patience. It didn’t seem like they were here to find food. Nor did they have

the patience to bite anyone. Left to themselves, they’d quickly haul in

particles of mud and built nests here and there in the house. You could try

scuttling them with a broom, but they’d get into a mad frenzy and climb up the

broom and on to your arm. Before you knew it, they’d be all over you, even

under your clothes. For days on end there would be a terrific invasion, and

then one day you’d wake up to find them gone. There was no telling why they

came, where they went. I sometimes saw them racing in lines along the window

sill in the front room, where there was nothing to eat. Perhaps they were on a

mission of some sort, only passing through our house in self-important columns.

But not once did I see the tail of a column, an ant that had no other ants

behind it.

After the marriage, Anita senses

the fault in the family ties and foundation, and therefore there is always a

constant tension between the three women of the house. Now, the nouveau riche

family is concerned about the comfort of Chikkappa, as he is the sole

breadwinner of the family. The narrator himself fears losing his inheritance

from his father, and doesn't want to get apart from the riches2 and

prosperity his uncle has brought in the house, without him doing almost nothing.

A dissent to the family virtues and well-being, Anita uses subtle verbal

insults, undermines, pokes, challenges their way of life or make fun of whomever

she wants and things which she doesn't find agreeable, and as if to rescue the

family the narrator's mother and sister too join the verbal row; this is what

the narrator escapes from often.

2. It’s

true what they say – it’s not we who control money, it’s the money that

controls us. When there’s only a little, it behaves meekly; when it grows, it

becomes brash and has its way with us.

The narrator candidly talks about

his thoughts, intentions, dark motives and personal failures, as if he accepts

it all, but is still at loss. It seems the family has accepted the way things

are and doesn't want to change in any way. Meanwhile, Anita resents the family

ways and how things are: an uncle who works day and night to maintain the

family business; a mother who is limited to the kitchen and can become ruthless

if it comes to saving the family values; a father who has less and less say

about anything in the family and whose jokes aren't appreciated by anyone; a

sister who has left her husband, come to live with her parents and has her own

private world, and a husband who is freeloading to the family fortune and

virtually does nothing. Ghachar Gochar, a word created by Anita and her brother

during their childhood, which means entanglement of things, has become a

reality to the narrator, who finds himself in the middle of a war of words ever

present in the household between the three women, family values, fear of losing3

the riches and expectation from his wife for him to be independent. It seems

that not only their freedom, but their fate and shame too are rooted in the

family ties. As if the family has learned to live in harmony amid the

dependence, tension and chaos.

3. A

man in our society is supposed to fulfil his wife’s financial needs, true, but

who knew he was expected to earn the money through his own toil?

In Ghachar Ghochar, we witness

the family and personal secrets being laid bare. We also closely observe the

changes in their way of life, of a family as they leap onto the higher social

status with a bond and understanding – that is reluctant to change – to such an

extent that the whole members are in a sort of symbiosis or have become

parasitic. In doing so, their own personal choices have been defined or are

limited by those unspoken virtues. The story is a dramatic view of a nouveau

riche family, but is not limited to this. It also unveils the dark motives that

run in a family. Here, it is a fear of losing the prosperity – which also has

deformed the personalities of few. To some extent, we can extrapolate the story

to those women who stand against violence and traditional ways, and are under

threat from their own families and sinister ways. Ghachar Gochar takes us into

the core of a family and its crisis that we often know about but we do not

speak of.

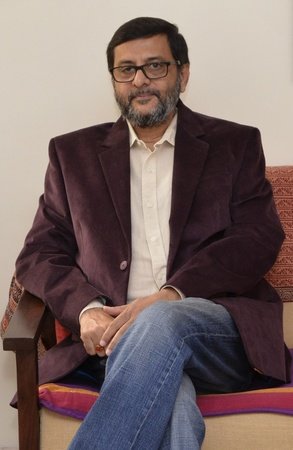

Author: Vivek Shanbhag

Translator: Srinath Perur

Publisher: Harper Collins Publishers (India)

Author's Photo Source: https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/authors/2136315/vivek-shanbhag

Review Copy Courtesy: Personal Copy

No comments:

Post a Comment